Crossing the finish line of the 2018 IRONMAN World Championship in Kona, Hawaii, was about as surreal a moment as I could have ever imagined.

Before I was invited to race, competing in it was about as realistic as me being in the Olympics or becoming an astronaut — as a slightly above-average high school swimmer and slightly below-average undergraduate engineering student, neither of those were ever in the picture.

As the volunteer at the finish line placed a finisher’s medal and Hawaiian lei around my neck, I couldn’t help but think about the long and winding road that led me to that extraordinary moment, a pivotal part of which was deciding to start living life as my authentic self: a gay man.

I grew up in a suburb of Springfield, Massachusetts, in a lower middle-class Catholic family of six. My mom and dad both worked blue-collar jobs at the Post Office. In different ways, they both had difficult childhoods, but at the core their struggle was the same: money and resources were scarce. When they met and became parents themselves, their single goal was to give their children a better life than they had, which meant a stable home, food on the table, a solid education and the occasional beach vacation.

Mom and Dad were good parents: they pushed us to do well in school, never missed a swim meet or soccer game and insisted on family dinner together at the kitchen table every night. But between their work schedules and the demands of four kids there wasn’t a whole lot of time for coddling or emotional connection in our house. As an overly emotional kid, I found this difficult and I knew from a young age that I was different. Lacking the words to assign what was different and the tools to work it out, this pushed me to be insecure and socially anxious.

Whatever it was that made me different felt like a weakness that needed to be hidden. I didn’t know what it was, but I was ashamed of it.

In order to gain the validation that kids so desperately seek from their parents and the external world, I invested an enormous amount of effort in other areas where I knew I could make my parents proud. I excelled in school, participated in countless extracurricular activities and played sports year-round.

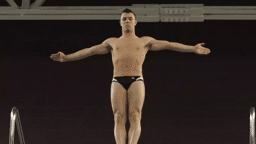

Swimming and diving were my most competitive sports; for a period of time, my name even appeared on my high school’s all-time record board. I lived for the applause I heard after tagging the wall at the end of each race or resurfacing from the water after a perfectly executed dive.

However, it was also in high school where I began to realize what that difference that I felt was. I found myself staring at my teammates on the pool deck or in the locker room out of the corner of my eye. In the mid-1990’s, I had been bullyied for years and my mom had a propensity to use the word “queer” to describe anything weird or different, so I knew my feelings were wrong but I couldn’t help it.

There was one unfortunate incident during a high school swim practice when I went down to the locker room wearing only my Speedo while and the men’s basketball team that was practicing across the hall went to the locker room at the same time. For the following week, my name might as well have been “fag” in the high school hallways when I passed by one of the school’s jocks.

I needed to escape these temptations as well as the threats my classmates posed to outing me despite me not even being able to accept that my sexual orientation was something other than heterosexual.

College was both a release and a relief. It was only an hour from where I grew up, but it represented a fresh start where I could reinvent myself. Though I didn’t attend an athletically competitive school, I was looking forward to competing at that level. Unfortunately, a knee injury before my first swim meet ended my swimming and diving career, so I diverted that time and energy into the most heteronormative activity I could think of: I joined a frat.

Fraternity life was great in so many ways: instant friends, housing that came with a cook, parties every weekend, and so on. It also a hyper-masculine environment where differences were not tolerated and the perfect place for me to further suppress any homosexual thoughts I was having.

After four more years of bottling everything away, I needed another escape and so I moved to Denver. “This was it,” I told myself. “No more dating women. You’re going to start living your authentic life.” Without the fear of running into family or friends on a date, I finally found myself dipping my toe into the world of online men-for-men dating.

Through dating, I became more comfortable with my sexuality and started to come out to my family: youngest sister first, then middle sister, then my brother. My parents came last. While my siblings were supportive and happy for me, my mom and dad did not take it well. While they didn’t get upset or say offensive comments, there was a definite wedge driven between our once-close relationship.

Luckily for me, right around this time my brother had suggested that we four siblings (now living in three different states across the country) meet up for a vacation and run a half-marathon together. I had never run a road race before and running wasn’t part of my fitness routine at that time, but we all agreed and booked our spots for the January 2010 Disney World half-marathon.

It turns out that running was the medicine I needed for the hurt I was feeling from my parents. Open miles on the roads and trails just outside of Denver gave me the space to both clear my head and work through my emotions. During some runs I would cry and on others I would feel such a sense of empowerment that I could have taken on the world.

It was on one of those runs that I finally worked through the words I needed to say to confront my parents about how I was feeling about our strained relationship. Running had become the therapy I needed to help figure out who I was and, more importantly, accept that I was OK.

After the Disney World half-marathon, I was bitten once again by the competition bug. Crossing the finish line brought on a feeling like none other: accomplishment, relief, pride, euphoria. I immediately signed up for another one and then my first marathon and then a second one of those. I just couldn’t get enough racing.

With my personal relationships improving, dating life going wel, and race training progressing, I was quite happy with the life I had settled into. Work was the only place where I was still closeted, though my close friends there knew I was gay and accepted me with open arms.

I was content with my situation. However, after a string of homophobic comments made by both co-workers and suppliers’ representatives, I found myself both coming out to my boss and HR and demanded that things change. Their response was no response and I realized it was time for me to go find a more inclusive and supportive culture.

I moved on and joined WhiteWave Foods, a company that celebrated my diversity and even supported my efforts (along with a few other colleagues) to start an LGBTQ+ resource group funded with corporate dollars. Up to this point in both my professional career and amateur sport career, I had found a lack of gay or otherwise LIGBTQ+ role models so I decided that if I couldn’t find that for myself, I was at least going to make sure that I became that for someone else.

WhiteWave proved to me that I could bring my authentic self to all aspects of life, and it also opened up career doors that eventually took me to Clif Bar in San Francisco and then Amazon in Seattle, two other companies vocal in their support of the LGBTQ+ community. By the time I’d arrived in Seattle, I was ready to graduate from marathons and try something even more challenging, and after a running two ultramarathons a friend dared me to sign up for an IRONMAN triathlon.

I hadn’t been on a bike or swam laps in years, but I was in good shape, so I said why not? Six short months later, I endured the most humbling day of my life as I battled the heat and hills of the 2018 IRONMAN Canada race in Whistler, British Columbia. I stumbled across the finish line with minutes to spare before the cutoff, but I had done it: I was an Ironman!

I may have latched onto sport at such a young age initially as a means to seek validation, but it led me on a path to not only fully accept who I was as a person but also accomplish something so few people can say they did. For that, I was proud.

I returned to work the following week and learned that Amazon happened to be the title sponsor of the upcoming 2018 IRONMAN World Championship race. With one free entry available and 11 weeks until race day, I was presented with the chance to compete alongside the world’s best athletes. It’s an honor typically only bestowed upon those who finish in the top few spots of other IRONMAN races throughout the year. What an incredible, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, and had I not walked away from my first job in pursuit a more welcoming culture all those years ago it never would have happened.

IRONMAN Hawaii was nothing short of incredible, and the experience has indebted me to the organization and sport for life. Many amateur athletes, myself included, use sport and training to manage the stresses of everyday life. I personally benefit from following structured training programs that lead up to big races, and it was difficult to have three full IRONMAN races that I had planned get canceled due to Covid-19 over the past 14 months.

As each of my planned events was canceled one or two months out from race day, I found myself spiraling, lost and falling away from fitness. But I also realized that I had an opportunity to help others who were struggling with the same mental health challenges that I was. This epiphany led me to leave my career in pursuit another one aimed at bettering the lives of others through physical and mental fitness.

As the U.S. starts to return to normal, I’m looking forward to showing up at my first post-pandemic race more than anything else. As LGBTQ+ people, we’re never really done coming out.

Being gay and being an athlete are both such important parts of who I am, and I yearn for more representation in the sports that I love. Representation matters, so I never go back into the closet when join a new run club or meet other competitors on race day.

Queer people belong in sport and if me showing up at the start line out and proud inspires just one other person to start living their life more authentically, then that’s worth more to me than any medal hanging on my walls.

Michael Lalli, 35, is an IRONMAN triathlete and marathon runner who lives in Austin, Texas. He recently left his job as a Director of Project Management for a major better-for-you snacking company to pursue a new education and career in Sports & Nutrition Science, through which he plans to carry out his personal mission of helping people live happier, healthier lives. He can be reached via email ([email protected]) or on Instagram @michaelraymond.

Story editor: Jim Buzinski

If you are an out LGBTQ person in sports and want to tell your story, email Jim ([email protected])

Check out our archive of coming out stories.

If you’re an LGBTQ person in sports looking to connect with others in the community, head over to GO! Space to meet and interact with other LGBTQ athletes, or to Equality Coaching Alliance to find other coaches, administrators and other non-athletes in sports