Perhaps you appreciate the aesthetics of gymnastics or acknowledge the inherent homoeroticism of wrestling. Maybe you’ve eyed the glistening torso of a Tongan flag-bearer or cheered at the campiness of a closing ceremony.

As the number of LGBTQ+ athletes competing at the Summer Olympics has shot up in the last two decades, possibly you’ve joined the growing queer audience tuning into the quadrennial Games.

And if there was a moment in your formative years when seeing the Olympic Games helped you to understand yourself, you might even be looking back on it now as a gay awakening.

For so many gay men, in particular, that awakening involves diving. A combination of fit men wearing a small dash of fabric, as well as a trickle of out divers, has made the sport an iconic symbol of queer interest in the Olympics.

Get off the sidelines and into the game

Our weekly newsletter is packed with everything from locker room chatter to pressing LGBTQ sports issues.

Tom Daley’s rise from teen to twunk has kept him on everyone’s radar.

Matthew Mitcham crying poolside in 2008 and then celebrating with his then-boyfriend as he alone beat the Chinese in their pool with the highest-scoring dive in Olympic history still brings tears to queer eyes.

For many others, it was watching icon Greg Louganis wow the world on the diving board.

Before he became an avowed “Olympaholic,” attending multiple Games all over the world as a volunteer or reporter, a young Charley Cullen Walters would watch hours of coverage from the front room of his home in St. Paul, Minn.

“Even at 5 years old, I was glued to Los Angeles ’84,” Walters, now a notable sports personality, journalist, and producer, told Outsports. “My parents frequently say they could not pull me away from the screen.”

Charley’s dreams took flight, and by Seoul ’88, he was “obsessed with the pageantry and celebration” of this grand spectacle and its global reach.

“I had a video game with all the main Olympic sports — you could choose to represent any country, and I was fascinated by that part, too. I promised myself I’d go to a Games one day. I was just so into it.”

His admiration lay with individual Olympians who transcended the occasion, like glamorous sprint queen Florence Griffith Joyner — the shining star of track and field in Seoul — and Matt Biondi, at the peak of his powers in the pool where he swam to a magnificent seven medals.

However, one American athlete caught his attention: Louganis, who won two diving gold medals in Korea, replicating his success in Los Angeles.

“I remember looking at Louganis and thinking, there’s something really relatable about this guy,” says Walters. “Honestly, it wasn’t just because he looked great in his Speedo! I found his whole story very interesting. I couldn’t put my finger on it, but I know I was rooting for him in particular.”

The size of Team LGBTQ — the collective number of out queer Olympic athletes, past and present — is significant. Today, we know of more than 600 participants from past Summer Games who are out. Many were not out publicly when they competed, but each has helped pave the way for the record levels of visibility expected in Paris this summer.

Related

Team LGBTQ at the 2024 Paris Summer Games

The list of out gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer and nonbinary Olympians will continue to grow.

By Outsports | June 28, 2024

It’s a far cry from the 1980s, when homophobic attitudes, exacerbated by the HIV/AIDS crisis, meant gay athletes like Louganis had little option but to stay closeted. Yet the inexorable rise of Team LGBTQ has been decades in the making. Thanks to a marathon effort that continues alongside the ongoing global fight for LGBTQ+ rights, the Olympics can be considered the queerest of all sporting events.

For LGBTQ+ medalists, visibility can bring an additional sense of accomplishment. After winning gold in Beijing, Mitcham told the BBC, “No one will ever be able to take away the fact I was the first openly gay male Olympic champion. It was the most amazing feeling and my proudest achievement.”

Nearly naked ambition and the beginnings of LGBTQ+ visibility

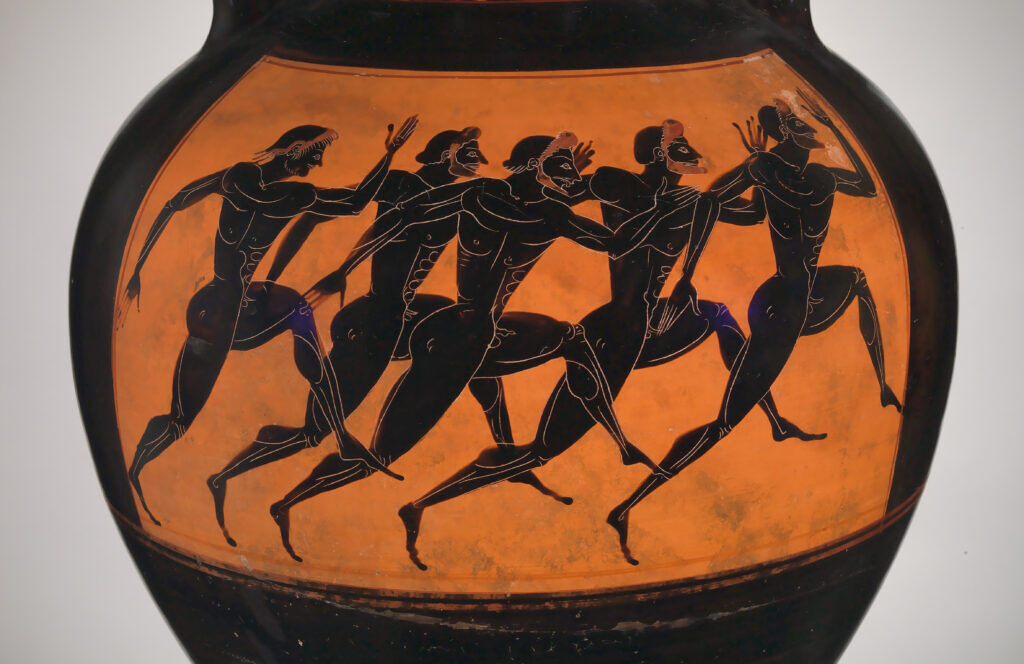

Athletic excellence and the promotion of self-esteem were important to the ancient Greeks. The Olympics showcased beautiful bodies and healthy minds in its original men-only version.

The finest specimens would gather at Olympia, parading unclothed to the delight of thousands of spectators (the word “gymnasium” derives from gymnos, meaning naked), with the most striking and successful athletes revered as demigods.

Champions were also immortalized and fawned over in the work of sculptors and poets. These were the thirst traps of their time — your favorite Instagram hotties from Paris 2024, such as Tom Daley, Arthur Nory, Robbie Manson, and Rayan Dutra, are continuing a tradition.

Meanwhile, with same-sex activity and pederasty the norm, a swathe of admirers were on the lookout for potential boyfriends. However, none of these men would consider themselves “gay” in the modern sense of the word.

Historian Tony Scupham-Bilton has documented several pairings from more than a thousand years of age-old Olympiads that were queer, such as that of Diocles of Corinth — winner of the stadion race at the 13th Olympics in 728 BCE — and his lawmaker lover, Philolaus.

They moved to live together in Thebes, a city where adult male lovers were more socially acceptable. You might say the athlete and the advocate — the Daley and Dustin Lance Black of their day.

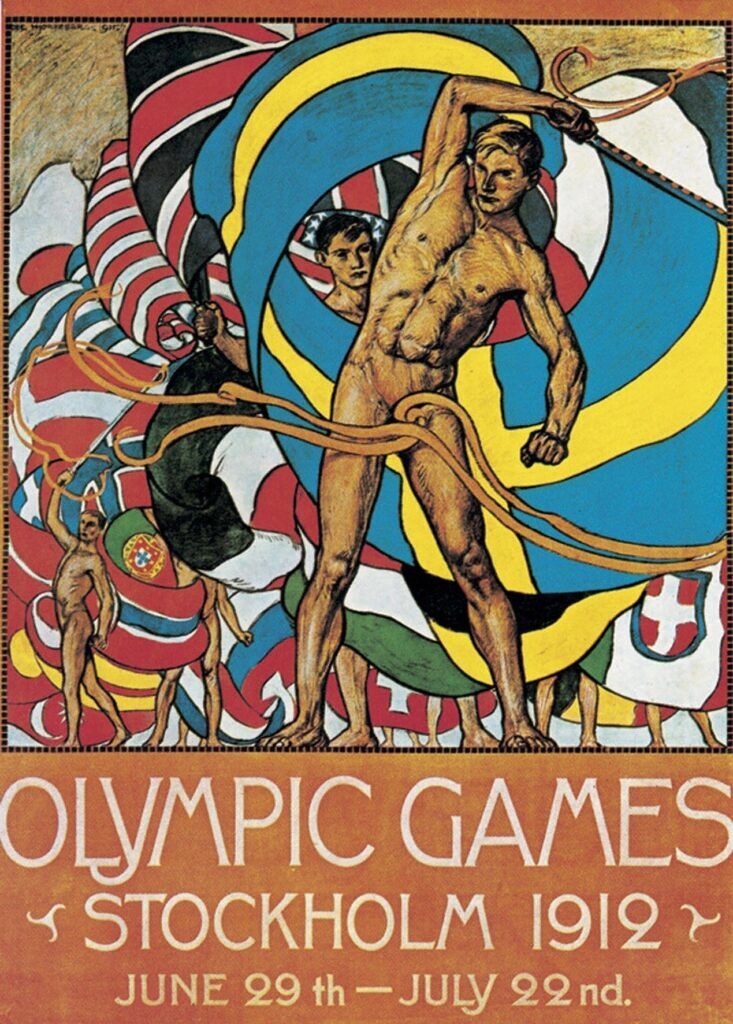

Fast-forward to the early 20th century, when promotional advertising featured lean male torsos, nodding back to the “Games of Antiquity.” The central figure on Olle Hjortzberg’s Stockholm 1912 Olympic Games poster has only a swirling ribbon to protect his modesty.

After World War I, male nudes remained prominent on the posters for Antwerp 1920, Paris 1924, and Amsterdam 1928. Little effort was made to appeal to women, who were beginning to compete in more significant numbers but made up less than a tenth of the total number of athletes by the end of the decade.

Sexism and lesbophobia discouraged female participation. In his research, Scupham-Bilton notes, “As more women took up sports, men began to describe them as ‘muscle molls.’ Male critics wrote derogatory articles in the press.”

Mildred “Babe” Didrikson Zaharias, winner of two gold medals and a silver in track and field at L.A. 1932, is today considered a pioneer for LGBTQ+ sportswomen. However, she was unable to embrace that status at the time.

“Her lack of self-acceptance and articulation was a loss to a generation of lesbian women who yearned for a self-proclaimed lesbian hero. But that was not a burden she chose to bear,” wrote biographer Susan E. Cayleff.

As for the earliest identified gay male Olympian, Scupham-Bilton’s research lists Danish tennis player Leif Rovsing, who competed in Stockholm in 1912.

Denmark legalized homosexuality for adults in 1933, but it remained illegal across the border in Germany, where the Nazi persecution of gay people was escalating by the time of the 1936 Berlin Olympics.

Previously, the capital had been home to a thriving queer scene, but the fascist regime swept that away. The lifesize nude statue Decathlete by Arno Breker, a sculptor commissioned by Hitler to evoke Aryan athletic ideals, was part of the propaganda art used to symbolize the superiority of race.

After World War II, there was scant evidence to suggest the Games were queering up.

We know of only around 20 LGBTQ+ athletes from the eight summer editions between 1948 and 1976. Most of that group are women, who were a small percentage of athletes overall.

As for the men, several would go on to participate in the Gay Games, including its founder Tom Waddell, who placed sixth in the decathlon in Mexico’s 1968 Summer Games. Waddell wanted to call his event the “Gay Olympics” to help break down stereotypes and promote inclusion in sports but was thwarted by a lawsuit filed by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) shortly before the inaugural 1982 event in San Francisco.

Three of these male Gay Games entrants were former Olympic swimmers: Paulo Figueiredo (Brazil), Peter Prijdekker (Netherlands), and Mark Chatfield (USA). Chatfield told the New York Times that he felt he could never have come out at the height of his career as he feared losing his place on the team, saying of the Gay Games, “It gave me a chance to have a reason to swim again.”

Still, even decades ago, gay athletes had a way of finding one another in the athletes’ village. In his autobiography Breaking the Surface, Louganis writes about his first serious crush, an “absolutely beautiful” Russian diver with whom he shared an affectionate encounter on a rare evening when their teammates weren’t hanging around.

It’s a rare glimpse into queer love in sports at a time when homophobia was so prevalent in broader society. Yet it would be another 12 years — those 1988 Olympics — when we saw the first publicly out gay man compete: equestrian Robert Dover.

More subtly, though, a queer eye was beginning to gaze upon the Summer Games, and it had a cultural influence that was far-reaching and fabulous.

A world of pageantry that would make RuPaul blush

The “pageantry and celebration” that so fascinated Charley Walters as a child can primarily be found in the Olympics’ opening and closing ceremonies.

These over-the-top, extravagant events offer an explosion of color and energy, often sprinkled with queer stardust. Factor in the huge scale of the productions, and you can see how they hold the power to transport attendees and TV viewers into a world filled with creative expression.

Examples of the ceremonies’ queer maximalism include Barcelona 1992, soundtracked by Freddie Mercury’s soaring duet with opera singer Montserrat Caballe, and including dynamic movement by choreographer Harrison McEldowney, featuring flamenco dancers and fantastic beasts.

In 2000, Peter Morrissey designed colorful gowns and garments for the Arrivals segment of Sydney’s opening ceremony, reflecting Australian multiculturalism at the turn of the millennium. “Eternity,” a tribute to Australia’s industrial revolution, followed by thousands of muscle-bound performers outfitted in plaid work shirts, tap dancing as sparks flew at their feet. Like Morrissey, this segment’s director, Nigel Triffitt, was also an out gay man.

But for those craving high camp, the consensus among seasoned Olympic observers is that Sydney’s closing ceremony takes the crown.

The proceedings began with Savage Garden performing their hit song “Affirmation” — which includes the lyric “I believe you can’t control or choose your sexuality” — and ended with Kylie Minogue in a shocking-pink showgirl costume singing “Dancing Queen.” The celebratory event also featured 50 drag queens parading alongside a replica of the titular bus from The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, itself dragged up with giant fake eyelashes and plump lips,

Thomas Jolly, artistic director of Paris 2024, continues to carry the LGBTQ+ torch and has pledged to create ceremonies in which “everyone can feel represented.” But for outright Olympics queerness, that night in Stadium Australia 24 years ago remains the benchmark.

Related

Olympics ceremonies director, who is queer, says he wants ‘everyone to feel represented’

Thomas Jolly will deliver the opening ceremony and closing ceremony at the Olympic Games that are “a celebration of life”… with Lady Gaga?

By Jon Holmes | July 12, 2024

‘Gay people are everywhere,’ including on the Olympic podium

Ioannis Melissanidis was among those revelers in Sydney. “I was jumping around, partying, flirting with guys!” he told Outsports. Four years before, at 19, he won floor exercise gold for Greece — the youngest male gymnast to become an Olympic champion.

He considered himself to be openly gay at the 1996 Atlanta Games, but saying so on social media wasn’t an option back then.

“I never came out because I’ve never been hidden,” he recalls. “For the ones that asked, I always had a straight answer — that’s my life. Like it or not, I don’t care.”

Melissandis experienced homophobia along the way, but very rarely from other athletes whose respect the gymnast had earned. After his success in Atlanta, however, some members of the Greek media turned against him. During the Sydney Games, a tabloid journalist wrote a scurrilous story suggesting the gymnast was in an inappropriate relationship with his coach. Other outlets ran with the lie, too.

“It was disgusting, but I was strong enough to defend myself,” he says. “Nowadays, we would call it hate speech, but back then, it felt like everybody could say whatever they wanted.”

Elsewhere, however, emerging digital LGBTQ+ media were applauding out Olympians, recognizing how they were helping to break down barriers.

By the Sydney Games, Outsports tracked the fortunes of several LGBTQ+ athletes, including medal winners Mia Hundvin and Camilla Andersen, two handball players in a civil union at the time. The couple even faced off against each other on the court when their respective countries, Norway and Denmark, met in the group stage.

“I never came out because I’ve never been hidden. For the ones that asked, I always had a straight answer — that’s my life. Like it or not, I don’t care.”

Olympian Ioannis Melissanidis

For Athens 2004, visibility was increasing.

“Gay people are everywhere,” equestrian Dover previously said. “Many of them aren’t out because they’re focused on their job during this time when sports is the number one thing in their lives.”

That was how Mathew Helm saw it, too. The Australian diver was out to his team during the Sydney and Athens Games; he won silver and bronze medals at the latter. But he wasn’t on the media’s radar.

“My time in sports was really focused on the diving and wanting to be special,” the former world synchro champion told Outsports. “It just so happened that I was a gay man as well, but I didn’t come out and make it public. A lot of that might have been because of stories I’d heard around that period. But I wasn’t closeted or ashamed of who I was either. I don’t reflect on that in a negative way, but I do wish that maybe I could have celebrated it a little bit.”

Stereotypes about masculinity in sports mean visibility is still limited for gay and bi men, who amounted to 17 of the 186 out athletes at the last Summer Olympics in Tokyo. A ratio of one man to eight women is expected on Team LGBTQ is expected this year.

Helm, who will be in Paris working as a coach, believes more support is now available for young male athletes who may be struggling with their sexuality. Having role models helps, too, he says.

“People like Matt Mitcham and Tom Daley opened up the door for others to come forward and be accepted.”

‘Out and proud,’ more than 140 LGBTQ+ Olympians descend on Paris

The expansion of women’s team sports at the Games has notably boosted the overall tally of LGBTQ+ athletes. A by-product of this has been increased athlete advocacy — for example, Megan Rapinoe, Seimone Augustus, and Natalie Cook were all out in London in 2012 and went on to become activists for equal marriage and broader LGBTQ+ rights.

Sue Bird already had four Olympic titles when she started dating Rapinoe in 2017. She won her fifth gold medal in Tokyo — her first as an out athlete — after their engagement, telling Time, “The more people that come out, that’s where you get to the point where nobody has to come out. Where you can just live. And it’s not a story.”

Kristen Thomas was also in Tokyo, representing the U.S. in rugby sevens. A traveling reserve for Paris 2024, Thomas, who identifies as nonbinary, is proud to be part of queer progress at the Games.

“Visibility is important,” Thomas told Outsports. “I hope seeing me out and proud gives other gender nonconforming people pride, and in some small way, it impacts treatment and acceptance of other nonbinary people.

“We just want to exist and be happy. I hope more people realize the humanity of Black queer people and celebrate the differences instead of seeing them as things to be changed or attacked.”

More than 200 nations will send teams to Paris 2024 for the sixth consecutive Summer Games. Within that diversity, queer athletes and fans will make sure Team LGBTQ’s presence is felt — and it’s those visual, viral moments that we’ll all remember:

In Rio, Brazilian rugby player Isadora Cerullo proposed to her girlfriend on the pitch. At the same time, British race walker Tom Bosworth asked ‘Will you marry me?” to his boyfriend on Copacabana Beach.

In Tokyo, Team USA’s Alana Smith showcased their pronouns on their skateboard and on a pin badge; Raven Saunders took a stand on the podium in support of mental health and intersectional awareness; and in his media conference after winning synchro gold, Tom Daley said simply but decisively, “I am a gay man and also an Olympic champion.”

Let’s hope for a similar feel-good factor in the French capital. Progress would be welcome, too. The record-high 186 out athletes at the last Summer Games hailed from 30 countries, less than 15% of the 206 represented. There is still plenty of room for growth.

Charley Cullen Walters wasn’t in Tokyo. (Travel restrictions prevented him from attending.) As a result, he concedes he’s at childlike levels of excitement for Paris, posting on Instagram in front of the Eiffel Tower: “Faster, Higher, Stronger… And Together… C’est Parti… Here We GO!”

“Together” has been added to the Olympic motto since Tokyo, and Walters sees its significance. In an increasingly divided world, he wants everyone, everywhere to feel as entranced by the Olympics as he did in the 1980s.

“It’s where I see humanity at its best,” says Walters, “a chance to overcome our obstacles and finally celebrate.”

Featured image: (l to r) Greg Louganis, Raven Saunders, Megan Rapinoe, and Brittney Griner. Photos: Tony Duffy/Getty Images, Andrew Nelles/USA TODAY Sports, Andrew Nelles-USA TODAY Sports, Pan Yulong/Xinhua/Getty Images. Photo Illustration by Kyle Neal for Outsports.